Included in collection: Business Management

Project Management Lecture

1.0 INTRODUCTION

“Project Management is no longer about managing the sequence of steps required to complete the project on time. It is about systematically incorporating the voice of the customer, creating a disciplined way of prioritising effort and resolving trade-offs, working concurrently on all aspects of the project in multi-functional teams and much more…….. Getting the project management process right should be a key strategic priority for every firm”

Professor D.T. Jones

(Foreword - Maylor, 2010)

Within most organisations, projects are essentially used to capture any number of improvement or development initiatives that sit outside the concept of normal, day-to-day business. Consequently, the nature of projects and the associated processes used to manage them are extremely diverse with huge differences in terms of complexity, scale, technology applications, success criteria, duration and speed of implementation (Slack, Brandon-Jones & Johnston, 2016).

Despite this variety, there can be a significant amount of commonality in the field of project management. From the outset, it is essential to identify and understand the key characteristics of a project and what the implications of it being taken forward will be - in essence, what is the ‘end state’ and what will ‘good’ look like? Next, it is vital to appreciate the operating environment for the project - who is involved, what their interests are and how they will be impacted by (and shape) the project. Finally, to take forward any project successfully requires the ability to balance different interests and objectives (hence the need to understand your stakeholders!), planning and controlling it effectively to achieve the objectives agreed (Morris, Pinto & Söderlund, 2012).

Given the complexities already highlighted, Project Management can be a challenging and difficult topic to study, with numerous academic references and practitioner guides available. This Chapter will seek to capture the key and common points in order to help guide further reading and the evolution of tailored, work-place project management practices.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

To be able to:

- Define project management and understand the key components.

- Understand the critical elements of a project plan and the importance of appropriate structures and frameworks.

- Possess an overview of some of the main project management methodologies and tools used.

- Appreciate the importance of review processes to the successful implementation and completion of any project.

2.0 DEFINING PROJECT MANAGEMENT - EXPECTATIONS, TERMS AND LINKAGES

Project:

“A temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product, service or result”

(Larson & Gray, 2011: 5)

The Association of Project Management (APM) believes that effective project management is the most efficient way to introduce enduring business change. A well-planned and executed project will adopt processes that seek to articulate and capture agreed benefits from the outset, whilst also putting in place mechanisms that monitor progress and delivery (APM, 2006). If this is the case, then the core components of any project must be able to:

- Define what is to be achieved, setting measurable performance targets which can be expressed in terms of time, cost, functionality and quality requirements.

- Identify the most appropriate project management tools and techniques to create a plan to deliver these outcomes.

- Use that plan to monitor, report and drive progress.

- Deploy people with the necessary skills and abilities with the authority and responsibility to deliver the outcomes demanded by the project. This is the Project Manager, who must also be accountable for the success or failure of the venture.

(Burke, 2010)

If we accept the definition offered, then a project does not form part of the normal day-to-day operation of a business. If it is also required to deliver some form of change (such as introducing a new product or service or building a new production facility), then we can begin to argue that project can share certain important characteristics:

- Although the same management methods and tools may be used, run by an established team, the projects themselves are finite in nature. Once the agreed objectives have been reached, then it becomes subsumed by normal business (e.g. new products and services become a part of the core business offering). Therefore a project must have clear (and agreed) start and end points.

- Each project is essentially unique. However, good project managers will seek to capture best practice from other (similar) projects, using established tools and techniques.

- As a project sits outside of normal business and seeks to deliver some form of change, there is generally a greater level of risk involved. Risk identification and mitigation therefore forms a central element of any project management plan.

- To deliver project outcomes and engage the broader stakeholder community that any successful change requires will involve the formation of a project team. Even with the smallest, most simple projects a manager will need to form ad-hoc groupings to achieve their aims. For large projects, the multi-disciplinary project teams required to deliver change often cause organisational stress and unease as they challenge established structures and working culture(s).

(Best Practice Management, 2009)

A UK Government standard exists - BS6079 - which has sought to capture all of these aspects and which seeks to create a useful guide for anyone embarking on the management of a project (BS6079, 1996). Before attempting to incorporate some of the tools and methodologies outlined later in this chapter, this provides a useful start point to the management of more routine, less complex projects.

Project Management:

“A unique set of coordinated activities, with definite starting and finishing points, undertaken by an individual or organisation to meet specific performance objectives within defined schedule, cost and performance parameters”

(BS6079, 1996)

As already noted, any successful project has to meet the needs and expectations of a range of stakeholders. Therefore, any project manager wishing to do well must establish who these stakeholders are (direct and indirect) and make sure that they have considered their needs and expectations from the outset. Only in doing so will they be able to clarify and confirm the purpose of their project, its scope and the objectives to be met (Burke, 2010). Of course, the real challenge for many project managers is that stakeholders and/or their requirements will often change throughout the life of a project!

Discussion Point:

Consider a personal/home project you may have been involved in. Examples could include decorating your house, buying a new car or planning a holiday.

What were the start and end points for your project and what objectives did you set? Which stakeholders did you need to involve and what was the composition of your project team? Was your project a success and (if so) how was that success measured?

2.1 PROJECT MANAGEMENT TERMS

Having sought to define and explain project and project management, you will note that other key terms are beginning to ‘creep’ into the language used. These can often create confusion or even an atmosphere of sometimes unwarranted or undeserved expertise when used liberally by project managers! Therefore, it is appropriate to capture some of the more common terms before exploring the subject further.

- Stakeholders. The people (and/or groups of people) who have an interest in a project and who may have an influence (or be influenced by) the projects activities. This influence may evolve or surface during the life of the project.

- Programme. An organisational framework used to group existing projects (as well as defining and implementing new ones) in an effort to focus and coordinate activities that deliver major benefits that reflect strategic objectives. Such coordination seeks to deliver business benefits that may not necessarily be realised if projects are pursued individually, whilst also helping to capture and share best practice. Programmes may last some considerable time, but still have a clear ‘end-date’ reflecting the overarching, more strategic objectives set.

- Portfolio. Whilst programme managers acts as the owner or sponsor of a group of linked projects, portfolio managers consider the relative priorities, resourcing and viability of projects. The intent is to seek synergies in resources and skills allocation in the delivery of projects, whilst a programme aims to synergise project objectives. Many organisations seek to manage this inherent tension by first creating operational portfolios of projects which then form part of a larger, more strategic programme.

- Benefit. Ultimately, a project is required to deliver some form of value - otherwise, why do it? This is not always considered in terms of a financial or operational return on investment as a project may yield some form of social or ethical gain, but whatever the measure the anticipated benefits of the project need to be identified. For most businesses, benefits need to be viewed from four key perspectives (and in the short, medium and long term) - shareholder (financial), customers/suppliers (at the very least, they should not perceive any dis-benefits!), internal (will the company function more efficiently/effectively?) and lessons-learned (what will we do better in the future as a result of this project?). Together, these perspectives can be combined to form the project’s value proposition and many company’s present them together using a balanced scorecard approach so that benefit trade-offs can be explored.

(Maylor, 2012, Slack et al, 2016)

2.2 THE CORE PROCESSES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Before examining tools and techniques in any depth, it is essential to recognise that any project possess generic elements across its lifecycle. In essence, it requires a start point, with established project initiation processes, it needs to be defined in scope so that the resources available and any constraints are understood in order to build realistic/achievable objectives. The project must be planned, monitored and controlled throughout its life and in closing the project there needs to be a mechanism to capture any lessons learned. (Young, 2000). Diagram 1 seeks to illustrate these generic/common elements which should provide further clarification as to the context of other widely used project terms:

|

Constraints time, cost, quality, technical and other performance parameters agreeing project scope |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Input business need, problem or opportunity The requirement |

|

Management of the Project |

|

Output Project deliverables and/or services, business change |

|

|

||||

|

Mechanisms People, tools, techniques, equipment, organisation agreeing project scope |

(APM, 2006)

Diagram 1: The Project Management Process

Get Help With Your Business Assignment

If you need assistance with writing your assignment, our professional business assignment writing service is here to help!

3.0 PROJECT MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

In considering how to take forward a project, a range of management processes and associated organisational concerns need to be addressed if the agreed benefits/deliverables are to be achieved:

- Maintaining constant focus on the agreed success criteria throughout the project, creating the means to monitor and measure how/when the required benefits are delivered.

- Stakeholder management. Through a systematic identification of stakeholders along with a supporting analysis of their needs and wants, the project creates engagement processes to deliver the outcomes defined.

- Value Management. Critically considering the resources needed to achieve the objectives outlined for the project and then potentially reviewing these objectives to see if a more optimal approach/solution can be developed.

- Planning. Documenting all the outcomes of the project planning process and then creating a comprehensive (reference) document to manage its implementation.

- Risk Management. Capturing and understanding project risks and then developing mechanisms that minimise threats and maximise opportunities to deliver the benefits required.

- Quality Management. Ensuring that what is delivered conforms to the required project outputs and is ‘fit for purpose’. Quality considerations are discussed in greater depth in Chapter 7.

- Health, Safety and Environmental Management. By applying appropriate standards and working methodologies, minimising the likelihood of the project causing accidents or exacerbating environmental concerns

(APM, 2006; Morris et al, 2012)

A significant number of methodologies have been developed in an effort to comprehensively address these concerns whilst still maintaining a coordinated/cohesive project management approach. It would be difficult to cover them all in this Chapter and wider reading is recommended, but the three most recognised/established methodologies are outlined - PRINCE2™, PMBOK® and Critical Path Analysis.

Discussion Point:

Review the personal/home project you ‘discussed’ earlier. Did you consider aspects such as risk, safety, quality and value in developing your plans? Did focussing on one of these areas mean that you were happy to compromise in others and was this a conscious process? Does making such compromises mean that your project is a failure?

3.1 PRINCE2™

PRINCE2™ is a professional standard, subject to accreditation processes, controlled and developed by the UK Office of Government Commerce (OGC). It is essentially a collation of best practice project management approaches and the OGC seeks to use the professional practitioner network to constantly evolve and develop processes as lessons learned are captured. Originally created to help manage large and/or complex projects, the perceived success of the PRINCE2™ model and the extensive practitioner network means that it is now regularly used for smaller, relatively straightforward activities (Molen, 2006).

PRINCE2™ seeks to build a framework that can be adapted by managers to reflect the specific demands of their project and the associated commercial/operating environment. A robust and comprehensive set of stepped elements and processes are outlined in order to allow for regular review points (‘gates’ or ‘gateways’) (Best Practice Management, 2009). These review points provide the main mechanisms for the control of projects, allowing for both progress review and to consider any changes to the scope of a project and/or the deliverables and objectives required (Morris et al, 2012). The core components of the PRINCE2™ are outlined in Diagram 2:

|

CORPORATE OR PROGRAMME MANAGEMENT |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

PROJECT MANDATE |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

DIRECTING A PROJECT |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

PROJECT BRIEF |

INITIATION DOCUMENT |

ADVICE |

REPORTS |

END STAGE REPORTS |

END PROJECTREPORTS |

LESSONS LEARNED |

|||||||||||||

|

STARTING A PROJECT |

|

INITIATING A PROJECT |

|

CONTROLLING A STAGE |

|

MANAGING STAGE TRANSITION |

|

CLOSING PROJECT |

|||||||||||

|

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ |

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ |

|

|

|

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ |

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ |

|||||||||||||

|

WORK PACK AUTHORISATION |

QUALITY CHECKPOINT WORK PACK CLOSURE |

||||||||||||||||||

|

MANAGING PROJECT DELIVERY |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

PROJECT PLANNING |

|||||||||||||||||||

(Morris & Pinto, 2004)

Diagram 2: The PRINCE2™ process

PRINCE2™ operates under a number of principles, with the most important being the requirement for a clear and agreed business case for the project. Roles and responsibilities have to be clearly defined, the demands of the wider operating environment should be considered and lessons must be both captured and learned/implemented. In managing the project through clearly defined stages, the essential focus on outputs and objectives is maintained. Throughout the life of the project, each review point considers the progress made to that stage against the criteria outlined in the business case (is it still wanted/needed?), organisation (are the right people involved?), quality (is it ‘good’ enough?), risk (what can go wrong?), change (what’s new or different since we started this project?) and progress (will we deliver on time and to budget?) (Best Practice Management, 2009).

Ultimately, PRINCE2™ is a linear approach that instigates regular review points (the gateway reviews) to evaluate progress and set go/no-go decision points. Unfortunately, these regular review mechanisms often allow the business and project control criteria being applied to change continually throughout the life of the project. This can mask the need to close a project if it is not meeting the original performance/objective criteria outlined, although the opportunity to consider changes in organisational strategy is a particular benefit. This reinforces the need to continually return to the original business case at each review point in order to ensure that the justification for the project remains valid (Morris et al, 2012).

PRINCE2™ is often regarded as the project management methodology demanded by businesses as there is a perceived benchmark to reach when recruiting and deploying project staff (i.e. are they PRINCE2™ qualified/accredited and do they understand the key terms and language used?). Admittedly, the linear control approach and the mandated gateway reviews do ensure that risks and any changes in project scope are robustly considered before the project progresses further. However, this does introduce a focus on control and management rather than innovation and creativity. This means that managing the project effectively can become the core output and many Government projects have been criticised for an almost institutional focus on the processes required rather than delivering the project objectives outlined in the business case (Morris & Pinto, 2004).

3.2 PMBOK®

PMBOK® - the Project Manager’s Book of Knowledge - is essentially an inclusive term used to describe the body of knowledge, skills and competences that resides within the project management profession (APM, 2006). Rather than taking a prescriptive, process-based approach (such as PRINCE2™), PMBOK® is a knowledge-based approach that seeks to provide project managers with considerable information about proven and successful project management approaches. Project managers are given greater latitude in how they apply this ‘best practice’ learning to their own business, although core process and knowledge areas are highlighted within PMBOK® in order to provide some structure (Meredith & Mantel, 2010).

PMBOK® argues that good and effective project management requires a balance between the application and deployment of knowledge, behaviours and processes. Experience is seen as being a particularly critical component as this generates both explicit and tacit knowledge and these aspects are explored further in Chapter 3.5. However, whilst PMBOK® provides project managers with the professional rigour and challenge they need, it does not provide the process standardisation many businesses require when taking forward numerous project simultaneously. Therefore, it is argued that it may be sensible to try and combine the two approaches i.e. to use PMBOK® as a mechanism to access the extensive knowledge base that exists in order to capture innovation and creativity whilst also using formal process models such as PRINCE2™ (Morris et al, 2012).

Discussion Point:

What do you think the potential challenges may be in trying to combine the methodologies and approaches of PRINCE2™ and PMBOK®?

Which approach are you likely to be more comfortable with and why? What are the key strengths and weaknesses of your chosen methodology?

4.0 PROJECT PHASES AND REVIEW

Returning to the key methodologies discussed above, the project phases and review points as outlined by both PRINCE2™ and PMBOK® are shown in Diagram 3:

|

PRINCE2 PROCESSES

|

APM PROCESSES

|

(Project Performance International, 2014).

Diagram 3: Project Phases and Review Points (PRINCE2™ and PMBOK®).

From a consideration of Diagram 3 and the issues highlighted around PMBOK® and PRINCE2™, it is clear that any effective project should be broken down into component parts to help ensure that the objectives set are realistic and achievable (Burke, 2010).

4.1 PROJECT INITIATION

From the outset, the ideas behind the project and the feasibility of delivering the anticipated aims need to be critically reviewed. This should include the identification of an owner - essentially the (internal) customer and the manager - who is going to be responsible for delivery. It is also essential to identify if the potential project has a broad base of support from those likely to be involved i.e. the views and aspirations of stakeholders (Newton, 2016).

A project proposal should be written (the PID for PRINCE2™ fans!) to address these issues. The project owner (or ‘sponsor’) evaluates this proposal and if they approve launching the project they are also responsible for allocating the required resources. Any proposal needs to address:

- Why the project is required. The key question here is what will be ‘better’ or ‘different’ as a result of this work being undertaken.

- The feasibility of the project. This should include a consideration of the resources needed (along with a comparison against the resources likely to be available!), the delivery method to be used

- Who the partners and stakeholders will be.

- Project scope i.e. what is ‘in’ and ‘out’. It is important to get clear agreement from the outset on what the project will actually deliver!

(Hubbard, 2017)

Many failed projects can attribute their perceived poor performance to a lack of work at this vital initiation stage. It is better to identify and resolve disagreements early (e.g. funding) and agree the scope from the outset. Often, the best project managers are those with the ability to say ‘no’ at this early phase e.g. by preventing ‘requirements creep’ as stakeholders seek to load more and more of their business aspirations onto the project. The work of the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) at the project initiation stage helped to ensure the delivery of a successful London 2012 Olympics (see the case study supplied with this Chapter). The end result of this phase should be the production of an agreed and resourced project plan (Newton, 2016).

4.2 PROJECT DEFINITION

Having gained approval to proceed with the project, it is now essential to capture all of the requirements it is expected to meet and create the clearest possible specification. This provides the detail that underpins the agreed scope and requires significant stakeholder engagement as well as the ability to understand different ways of thinking! (Larson & Gray, 2011). For example, a project manager may be working on a data storage project and talks to stakeholders about the need to create a central repository for all the company’s corporate manuals. As a result, one stakeholder may be thinking about a central library holding actual books, whilst another may be anticipating the delivering of a tablet computer with all the material in electronic format!

In defining the project the manager there needs to capture the requirements of end-users/stakeholders (what is needed - not necessarily what is wanted!) and translate that into project requirements. In doing so, they must identify any preconditions (e.g. legislative and regulatory requirements, organisational approval processes etc.), functional demands (e.g. quality aspects), operational requirements (how project success will be measured - what will be ‘better’) and design limitations (e.g. using mandated business systems, reflecting corporate CSR and ethical policies) (Burke, 2010).

Successful project definition requires a project manager able to effectively engage and collaborate with the stakeholders involved. For example, a key cause of project failure is often late engagement with end users/customers who end up receiving a product or service that reflects corporate expectations but not their own needs. Agreeing project requirements ultimately requires negotiation, but the aim must be to produce an agreed list as this becomes the defining parameters of the project (Hubbard, 2017). Once this has been agreed, customers and stakeholders should not be allowed to add more requirements as the project moves into the next phase.

Discussion Point:

Can you think of a product or service that was successfully delivered in terms of project management but which did not meet the requirements of customers? Would earlier customer engagement (at the project definition phase) have resolved these problems?

4.3 PROJECT DESIGN

Having considered the ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘why’ of a project, the ‘how’ and ‘where’ can now be examined. The project manager develops one or more designs focussing on the approach they will take to meet the agreed project requirements. The outputs of this phase will depend upon the nature of the project but can include prototypes, product sketches, building plans, flow charts (e.g. for a new customer service centre) and mock-ups of web pages.

The aim is to create outputs that provide an illustration of how the project will take the agreed requirements of stakeholders and turn them into project outputs/deliverables. As for the definition phase, once these have been agreed they should not be changed as the project moves into development (Maylor, 2012).

Get Help With Your Business Assignment

If you need assistance with writing your assignment, our professional business assignment writing service is here to help!

4.4 PROJECT DEVELOPMENT

At this stage, the mantra is about ‘prior preparation preventing …. poor performance’! Project schedules are developed, suppliers and contractors are engaged, personnel are tasked and resources are allocated to project elements. The aim must be to ensure that everyone involved understands what they will be expected to do, by when and how they are expected to do it. Critical dependencies should also be identified so that the flow of the project can be effectively managed i.e. what deliverable needs to be completed before subsequent work can begin (Newton, 2016).

4.5 IMPLEMENTATION

It is only at this stage that the project may become visible to others which reinforces the need for effective stakeholder identification and engagement from the outset. As the project gets underway, unexpected or unanticipated stakeholders can potentially emerge which could challenge the viability of the project.

As the project moves forward, its progress is evaluated in accordance with the agreed requirements and any schedules created during the design and development phases. Project managers also need to appreciate a basic military maxim - that no plan ever survives contact with the enemy! For complex projects, it is rarely possible to meet all of the precise requirements agreed. Compromises often have to be made (in terms of time, cost, quality and/or performance), but decisions around these compromises must involve the relevant stakeholders. Any agreed changes need to be properly documented and the implications fully understood, as they are amending project requirements (BS6079, 1996).

4.6 FOLLOW-UP AND CLOSURE

An agreed point of project closure is required, but before doing so consideration should be given as to the ‘follow-up’ activities needed to facilitate any handover from the project team. This could include the provision of training course and materials for a new product or providing a help-line for customers (Hubbard, 2017).

In closing a project, there should be a formal handover of responsibilities from the project team to the project owner or customer. The final project deliverable should be some form of ‘lessons learned’ document which outlines what went well, what went badly so that in future projects of a similar nature best practice can be carried forward and mistakes avoided (Burke, 2010).

Discussion Point:

It has been said that closing a project can often take longer than initiating and delivering the project itself. Why do you think this may be the case?

5.0 PROJECT MANAGEMENT TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

Work Breakdown Structure:

“A deliverable-oriented, hierarchical decomposition of a project into smaller components. Work breakdown structures are a key deliverable that break the work required to complete the project into manageable sections focussed on creating the defined deliverables.”

(APM, 2006)

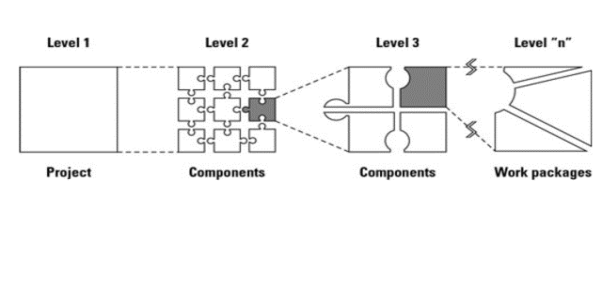

One of the key challenges for managers is the ability to maintain a holistic oversight of the overall project whilst also focussing on the detail required to meet all of the agreed requirements. Every project should possess some form of Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) that supports the management of this balance whilst also identifying how each distinct element of the work relates to other activities (APM, 2006). Diagram 4 provides an illustration of how the WBS should reflect the structure of the project:

(Portny, 2013)

Diagram 4: Work Breakdown Structure

In order to manage these complex project relationships, a number of different planning tools can used.

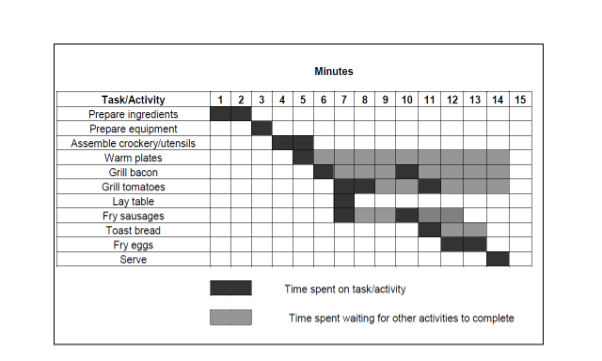

5.1 GANTT CHARTS

Gantt charts are ideal tools for scheduling work and provide an excellent visual indication to demonstrate project progress. Whilst they do not easily reflect critical interdependencies (see 5.2 below), they can be developed to illustrate activity types (through colour coding of various elements) as well as budgeting information. A simple GANNT chart is shown at Diagram 5:

(ILM, 2013: 18)

Diagram 5: Gantt chart - Making Breakfast

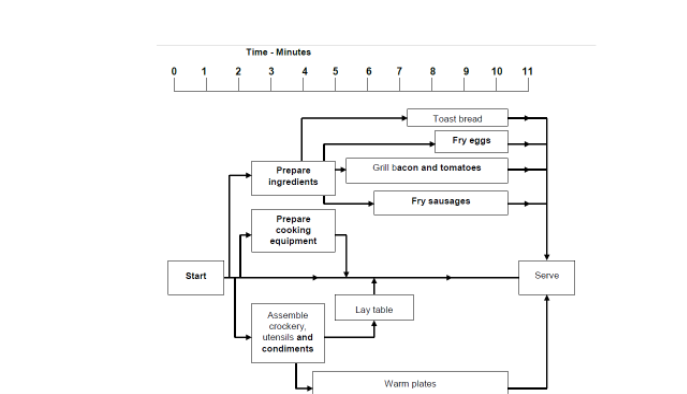

5.2 NETWORK DIAGRAMS AND CRITICAL PATH ANALYSIS

Project Evaluation and Review Techniques (PERT) or more simply ‘network diagrams’ are better tools for identifying the relationships between work activities. They enable project managers to identify areas of concurrent activity as well as important dependencies i.e. what areas of work need to be successfully completed before others can begin (Burke, 2010).

Being able to show the flow of work in relation to time allows the identification of the critical path - the longest sequence of activities in a plan which will need to be completed on time if the project is to meet its due date (ILM, 2013). Activities on the project’s critical path cannot begin until the previous work element has been completed.

PERT and Critical Path Analysis tools have developed in parallel and for today’s project managers there is often little difference in how they are applied. Further reading is advised in order to understand how to utilise these methodologies when considering complex projects, but for the basic example presented in Diagram 5, the network/PERT diagram and critical path could be shown as follows:

(ILM, 2013: 19)

Diagram 6: Network Diagram and Critical Path - Making Breakfast

In Diagram 6, each event (or milestone) is linked by ‘vectors’ (the arrowed lines) which represent the activity required and the direction of each arrowed line highlights the sequence of each task. Preparing the ingredients, cooking equipment and utensils do not depend upon each other and are therefore shown as parallel or concurrent tasks. However, grilling the bacon and frying the sausages are dependent (or serial) tasks as they cannot begin until the ingredients have been prepared and the cooking equipment is ready!

Discussion Point:

Consider Diagram 6 carefully. Have all the dependent tasks been correctly identified and linked? Where is the critical path?

6.0 THE IMPORTANCE OF THE BUSINESS CASE

It may seem strange highlighting the importance of the business case this late in the Chapter but this is intentional. This is to reinforce the importance of the prior preparation and knowledge application that is essential if any major project is to stand any chance of success. When crafting a business case as a part of project initiation and definition (see 4.1 and 4.2 above), the aim must be to lead any reader through your thought and decision processes in order to clearly demonstrate why your project is necessary and the options you have considered (Greasley, 2015).

As a minimum, any business case should consider/present the following:

- A clear statement about the problem being face and how this relates to the organisation’s mission, vision and strategy.

- An analysis of the issues to be addressed, demonstrating that you have identified and engaged relevant stakeholders.

- A review of the various options and courses of action that you have considered - remember that doing nothing is just as valid as doing something! This review should consider benefits, risks, costs and an outline timetable.

- A recommendation as to which course of action/option should be pursued as a project to address the issues identified in the business case.

- The lessons learned and ‘best practice’ identified from previous projects that will be taken forward if the business case is approved.

- Any other aspects required by internal approval and initiation processes (e.g. an investment appraisal).

- An outline of the anticipated project outcomes and deliverables (which will be refined during the design and development phases - see 4.3 and 4.4 (above)).

(Henry, 2011)

Get Help With Your Business Assignment

If you need assistance with writing your assignment, our professional business assignment writing service is here to help!

7.0 SUMMARY

This Chapter has only been able to provide you with an outline review of the core project management concepts and approaches. Whilst the basic building blocks and core processes are relatively straightforward, they quickly become extremely complex when issues such as critical dependencies and resourcing requirements begin to be identified. The tools and techniques available to support project managers are extensive, but at its heart successful project management is about leadership and coordination. The best project managers are not necessarily those that are able to deploy the latest software tools - it is the ability to identify, engage and communicate with key stakeholders that often proves to be the critical success factor. You are therefore advised to consider this Chapter alongside those addressing leadership, management, communication, knowledge and learning.

The personal skills of a project manager are also reflected in what ‘good’ project management seeks to deliver - negotiated and agreed outcomes, conflict resolution (between both stakeholders and objectives) and achievement. The key is to remain focussed on delivery rather than the processes involved, capture best practice and learn from past mistakes. However, as shown by the number of failed project examples contained within academic literature this is clearly easier said than done! Ultimately, the challenge is one of balance - understanding detail without losing sight of the overall project context and strategy whilst maintaining an appreciation of what the customer expects to receive.

Critically consider your capabilities as a project manager. Even if you have not formally undertaken the role in the workplace, if you accept the definition supplied in this Chapter you will have done so e.g. decorating, going on holiday, planning a conference etc.

What do you consider to be your strengths and weaknesses? What can you do to improve your performance as a project manager?

7.1 RECOMMENDED TEXTS

Morris, P.W.G., Pinto, J.K., Söderlund, J. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Project Management, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newton, R. (2016). Project Management, Step by Step: How to Plan and Manage a Highly Successful Project, 2nd Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

8.0 REFERENCES

APM. (2006). APM Body of Knowledge, 5th Edition, Princes Risborough: Association for Project Management.

Best Practice Management. (2009). Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2™, Norwich: The Stationery Office.

BS6079. (1996). Guide to Project Management, London: British Standards Board

Burke, R. (2010). Project Management: Planning & Control Techniques, 4th Edition, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Greasley, A. (2015). Operations Management, 3rd Edition, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Henry, A.E. (2011). Understanding Strategic Management, 2nd Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hubbard, H. (2017). Project Management: Proven Project Management and Project Planning Techniques To Complete Any Project Successfully, USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

ILM. (2013). ILM Level 3 Leadership and Management: Planning and Allocating Work Unit 8600-303, Sleaford: Ultimate Learning Resources Ltd.

Larson, E. W., Gray, C.F. (2011). Project Management: The managerial process, 5th Edition, Singapore: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

Maylor, H. (2012). Project Management, 4th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Meredith, J.R., Mantel, S.J. (2010). Project Management: A Managerial Approach, 7th Edition, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Molen, M. (2006). PRINCE2 for the Project Executive: Practical Advice for Achieving Project Governance, Norwich: The Stationery Office.

Morris, P.W.G., Pinto, J.K., Söderlund, J. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Project Management, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morris, P.W.G., Pinto, J.K. (2004). The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Newton, R. (2016). Project Management, Step by Step: How to Plan and Manage a Highly Successful Project, 2nd Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Portny, S.E. (2013). Project Management For Dummies, 4th Edition, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Project Performance International. (2014). Relationship between the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®) and PRINCE2™. [Online], Available:

http://www.ppi-int.com/prince2/prince2-PMBOK® -relationship.php [28 February, 2017].

Slack, N., Brandon-Jones, A., Johnston, R. (2016). Operations Management, 8th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Young, T.L. (2000). Successful Project Management, London: Kogan Page Ltd.

9.0 BIBLIOGRAPHY

APM. (2013). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th Edition, Princes Risborough: Association for Project Management.

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Related Content

CollectionsContent relating to: "Business Management"

Business Management describes the management of business operations and activity, including the planning, organisation, resource allocation, and implementation of efforts towards achieving their goals.

Related Articles

Strategic Business Management and Planning Coca cola Company

In the exact of science Business planning is often described as more than of an art. In organizations this becomes especially true when ones business plans revolve around the cycle of annual budgeting...

Technology in Business - Lecture Notes

This Chapter explores the impact of technology for business and the associated issues for society and consumers, focussing on developments......

Project Management Lecture Notes

This Chapter provides an outline review of the issues surrounding project management. A project is a temporary endeavour undertaken......

GBR

GBR